Pilot research: Social media-specific epistemology and its relationship with media literacy in Taiwanese and Vietnamese university students

Justification for Knowing stands out in terms of correlation with New Media Literacy. Taiwan college students perform higher prosumption media literacy than Vietnam students.

This is the extended text of our oral presentation at the APERA 2025 conference.

Chiang, Y.-C., Nguyen, H.-M.. (2025 November 1). Social Media-Specific Epistemology and its Relationship with Media Literacy in Taiwanese and Vietnamese University Students. [Conference presentation]. APERA-TERA 2025 International Conference. Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

Abstract

The study conducted among university students in Vietnam and Taiwan explored the relationship between social media-specific epistemological beliefs (SMEB) and new media literacy (NML). There were 101 participants in total, including 53 Vietnamese and 48 Taiwanese students. The participants completed validated scales measuring three SMEB dimensions: Simplicity and Certainty of Knowledge (SCK), Source of Knowledge (SK), and Justification for Knowing (JK), as well as four dimensions of NML: Functional Consumption (FC), Critical Consumption (CC), Functional Prosumption (FP), and Critical Prosumption (CP).

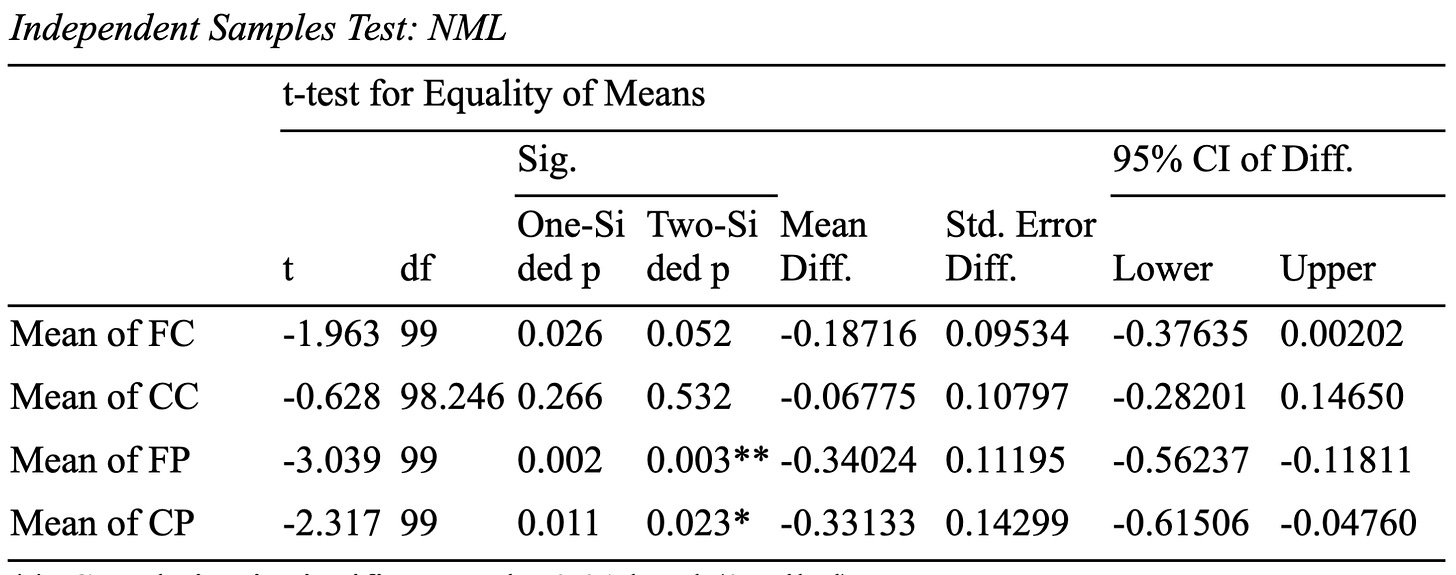

Pearson correlation analyses showed that JK was significantly and positively correlated with all four NML dimensions. In contrast, SCK and SK were not significantly correlated with any media literacy constructs. Independent-sample t-tests revealed that Taiwanese students scored significantly higher than Vietnamese students in Functional Prosumption (p = .003) and Critical Prosumption (p = .023). There is a difference in NML scores between the two groups of students. (p = .024)

These findings demonstrate the importance of Justification for Knowing in correlation with media literacy in digital environments and suggest potential cultural influences on how students engage in media production. The study contributes to cross-cultural epistemology research and may inform future media literacy interventions in higher education.

1. Introduction

In today’s social media environment, young people especially those in adolescence are increasingly exposed to conflicting truth claims and questionable authorities online. A primary concern is their vulnerability to “false authorities” (fake and unintended authorities) who spread false information instead of valid knowledge (Jäger, 2024). These so-called “false authorities” harm not only individual knowledge acquisition but also their development in perspective-taking, social-learning behaviors, and epistemological beliefs.

Though social media can be used to achieve various goals, including the positive ones, we’ve observed it used in improper activities. For example, spear phishing, political manipulation, digital hate speech, etc. (Mercy Corps, 2019). Particularly, social media has been used to spread disinformation and propaganda, which further achieve a variety of political, economic, or military objectives (Huang, 2020).

As media has evolved, critically interpreting, evaluating, and engaging with it has become increasingly important. Koc and Barut (2016) developed a conceptual framework to assess how well adolescents can navigate digital environments in which epistemic challenges are frequently encountered.

Adolescence is a crucial time in epistemological development. Chandler points out that relativistic epistemology emerges during adolescence. Because the development of meta-cognitive abilities and perspective-taking skills in adolescence is sufficient to lead to relativism (as cited in Pillow, 1999).

As Chandler notes, the emergence of relativistic thinking and the sense of uncertainty trigger an intellectual crisis that can manifest as dogmatism or skeptical doubt. That means adolescents face the uncertainty of the validity of one’s beliefs, coupled with their diverse ways of dealing with doubt. Furthermore, the proliferation of social media as a dominant source of information makes this process even more complicated.

Regarding the multidimensional epistemology model, much of our knowledge is not directly acquired but attained through others, especially those who are experts for issues we are not experts for (Bromme et al, 2010). Therefore, everyday epistemological issues related to improving judgments of knowing to understand how specialized knowledge is distributed (who knows what) and to evaluate expert sources (whom to believe).

This situation is more sensitive in online environments where authorities are often constructed through popularity rather than expertise. In King & Kitchener’s research on epistemic cognition (2012), it was identified that college students started to demonstrate quasi-reflective thinking. This means that late adolescents in this stage have the ability to accept the ambiguity of knowledge and critically examine the perceived information.

On the other hand, Sharon and Encarnación (2024) examine the growing decline in trust of emerging adults in major institutions such as business and government. Accompanying with the polarized digital discourse and media-saturated society, young people are confronted with epistemic development challenges, described as a sense of “vague(ness)” in their personal belief.

In this situation, epistemic relativism may lead to epistemic nihilism or echo-chamber thinking, thereby restricting the intellectual openness essential for mature belief formation. Moreover, analyzing adolescents’ epistemological beliefs without taking into account their level of media literacy may result in an incomplete picture. Because how they perceive authority and knowledge online may be influenced by their literacy in decoding and responding to digital content.

Given that personal epistemology and media literacy both touch on individuals’ cognition activities and perceptions, we would like to explore late adolescents’ epistemology beliefs regarding the social media aspect and its relations with media competencies.

RQ1) What is the relationship between university students’ epistemology beliefs on social media and their media literacy?

RQ2-1) Are there differences in university students’ epistemology beliefs on social media between countries?

RQ2-2) Are there differences in university students’ media literacy performance between countries?

2. Literature Review

2.1 Cultural–cognitive traditions

Hofer, B.K. (2008)) argues that research on epistemology should be considered about the sensitivity of cultural contexts in multiple aspects, as well as considering the changing nature of cultural influence. She cites in one cross-cultural study between Chinese and US students, the Chinese students showed different cognitive developmental patterns than the US students in the study. This result can be interpreted by the differences of cognitive development due to person-environment interaction complexity.

Furthermore, she also points out the translation issue when transporting in another culture. For example, a study of teacher education students in Hong Kong found that dimensions differed from the factors Schommer has identified in ways that were interpretable by culture (Chan and Elliott, 2002). While other research (Chai et al., 2006) claims for the cultural basis of beliefs and district nature of epistemic beliefs in Confucian cultures.

These informed the current study of the needs of investigating epistemology topics under different cultural contexts. While two researchers are from Vietnam and Taiwan, two Asian countries with very different culture, society structure, and political systems, we are curious if there is any difference in these two countries. After searching, we didn’t find many studies around country comparison in terms of social media epistemology, particularly in the two countries. This study was developed from this research gap.

2.2 The relationship between Media Literacy & Epistemology Beliefs

Studies of epistemology have developed the concept of epistemic thinking, which is related broadly to knowledge and knowing. This concept is referred to in numerous terms in literature, including personal epistemology, epistemological or epistemic beliefs, epistemic cognition and epistemological resources (Barzilai, S., Chinn, C.A, 2024)

Based on this concept, Chinn, C. A et al (2014) proposed the AIR Framework, which characterizes epistemic thinking through three interrelated components: 1) Epistemic aims refer to the purposes for which individuals seek knowledge, shaping their motivations and efforts in knowledge acquisition. 2) Epistemic ideals represent the standards used to evaluate whether these aims have been achieved and to assess the quality of the resulting knowledge. 3) Reliable epistemic processes are the strategies or methods individuals employ to pursue their epistemic aims in ways consistent with their epistemic ideals. (as cited in Barzilai & Chinn, 2024).

Celik et al. (2021) argued that epistemological beliefs play a crucial role in how individuals evaluate information on social media. Critically questioning the sources and credibility of information is an essential skill for individuals who are new media literate, and this evaluative process is greatly influenced by their underlying epistemological beliefs. In other words, a person’s beliefs about the nature of knowledge and knowing can shape how they engage with and assess digital content.

As conceptualized through the AIR Framework, new media literacy (NML), including critical consumption and prosumption, can be seen as a set of reliable epistemic processes. It is through these processes that individuals are able to navigate complex digital environments where epistemic challenges are common. As a result, the connection between personal epistemology and new media literacy becomes more clear: epistemological beliefs provide the epistemic goals and ideals that drive the development of advanced media literacy skills.

2.3 Digital landscapes in Taiwan and Vietnam

According to a survey report from the Taiwan Network Information Center (2024), the percentage of Internet users acquiring information from social media has been increasing in the past years. The majority of Taiwan’s issues in social media comes from the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) ambition due to these two countries’ special diplomatic relationship.

PRC, similar to some other totalitarian regimes, applies the concept of “Social Media Weaponization” (Waltzman, 2017; Singer & Brooking, 2018). Its goal is, by weakening Taiwan’s social stability, to further lower its international influence and ability to defend itself. There are several pillars of PPC’s social media strategy. For example, using social media to spread positive information about its image to the world. Or, leveraging platform algorithms to promote content and collaborate with foreign influencers to produce material that beautifies their reputation.

During the U.S.-China trade war, PPC’s Ministry of Foreign Affair used social media to “tell the story of China” and to “facilitate exchange and promote mutual understanding” (Huang & Wang, 2021). The U.S. government has officially warned the world that PPC has been trying to reshape the global information environment with social media strategies (U.S. DEPARTMENT of STATES, 2023).

As a result, Taiwan faces one of the most vulnerable digital environments around the globe. In a research conducted by the V-Dem Institute (2024), an international think tank, identified that Taiwan is the most-affected country by online disinformation in the world, followed by Latvia and Palestine. On the other hand, a report from Taiwan’s National Security Bureau (2024) stated that there were 2.4 million cyber attacks attempted per day on Taiwan in 2024, mostly conducted by PRC.

While Taiwan faces external threats, Vietnam’s digital environment presents a challenge from internal control to centralized regulation. The Vietnamese government focuses on shaping its domestic information space through strict media governance.

Vietnam operates under a highly centralized political system, where digital platforms and social media influencers are subject to increasing state oversight. Despite actively embracing new media technologies to foster economic growth and global integration, the country insists that these technologies adhere to state-imposed guidelines. For instance, all social media accounts with over 10,000 followers must register their contact information with government authorities. Platforms are also required to remove content flagged by officials, reinforcing the state’s control over online discourse (Le, 2022).

In May 2024, Vietnam’s Ministry of Information and Communications ordered domestic telecom providers to block Telegram access. The decision was made following allegations that 68% of the 9,600 Telegram channels and groups operating in Vietnam were involved in illegal activities, such as online fraud, drug trafficking, and even terrorist activities (Guarascio & Nguyen, 2024).

As Bui (2016, as cited in Le, 2022) noted, the balance of power in the Vietnamese digital space heavily favors the state and platforms, who ultimately determine what content is visible and allowed to circulate.

2.4 Media literacy

Many approaches and actions were raised in order to tackle the issue of social media information. One of the most recognized methods is through media literacy education/empowerment. Numerous scholars have provided theories and frameworks regarding media literacy and its corresponding skills. First, Chen et al. (2011) published a media literacy framework, which divided the media literacy skills into two dimensions — Prosuming v.s. consuming; Critical v.s. Functional.

Successively, Lin et al. (2013) developed an enhanced version of new media literacy (NML) based on Chen et al.’s study. It argued that the prior framework was vague with the exact skills. Lin and the fellow scholars developed a refined version of NML, which provides clearer definitions of NML under the four types. Under the four types, they developed 10 categories of media literacy. These then became a strong foundation of how future researchers look at media literacy.

In Vietnam, a quantitative study of 652 young people aged 18 to 30 found a positive correlation between media literacy and trust in government, support for anti-pandemic regulations, and vaccine readiness (Vu, 2024). These findings suggest that media literacy is shaped not only by individuals’ cognitive abilities or knowledge, but also by the broader sociopolitical context and level of social development. As the study argues, media literacy can function as an effective tool for pandemic management and serve as a type of social vaccine to end the infodemic, which is to combat the spread of misinformation during public health crises (Vu, 2024).

Because of the vulnerable digital environments, Taiwan has put significant efforts and resources into related education. Media literacy education has been integrated in its education policies. In the latest national curriculum guidelines implemented in 2019, one of the nine core competences is Technology and media literacy. In 2023, the Ministry of Education in Taiwan released the “Whitepaper of media literacy education in the digital age”.

3. Methodology

This study applies the quantitative approach as it enables us to examine the differences and relationships between variables. Two variables will be measured in this study based on our research questions.

3.1. Measuring Personal epistemology regarding social media usage

To understand individuals’ personal beliefs when it comes to social media, we use the social media-specific epistemological beliefs scale (SMEBS) developed by Celik (2019). This is the only epistemological scale specifically developed for the social media domain that we are aware of. Three factors were identified as the result of a 15-item scale. They are Simplicity and certainty of knowledge (SCK), Source of knowledge (SK), and Justification for knowing (JK).

Some examples in the scale include “A problem that is discussed in social media has more than one correct answer.” (SCK), “The knowledge in a subject shared by a person with more followers on social media is more trustworthy for me.” (SK), and “I check whether the knowledge I read on social media is logical or not on different Internet sites.” (JK).

3.2 Measuring Media literacy

Koc & Barut (2016) developed a new media literacy scale (NMLS) to understand the media literacy performance of university students. It applied the new media literacy measuring framework from Lin et al. (2013), which consists of two dimensions, four aspects. The 35-item questionnaire includes questions across Functional consumption (FC), Critical consumption (CC), Functional prosumption (FP), and Critical prosumption (CP).

Example questions include “I know how to use searching tools to get information needed in the media.” (FC), “I am able to determine whether or not media contents have commercial messages.” (CC), “It is easy for me to create user accounts and profiles in media environments.” (FP), and “I am skilled at designing media contents that reflect critical thinking of certain matters.” (CP).

3.3 Survey Process

Two questionnaires are implemented in the form of an online survey (Google form). The survey contains three parts - Participant demographic information, Social media-specific epistemology, and social media literacy. Survey forms were distributed to the universities students with researchers’ connection for convenient sampling. On Vietnam’s side, ten (10) universities in Ho Chi Minh city were surveyed. In Taiwan, two (2) public universities, one in Taipei (northern Taiwan) and one in Kaohsiung (southern Taiwan), were surveyed.

Given that both questionnaires are originally in English, researchers utilize generative AI translation tools to translate the items into Traditional Mandarin and Vietnamese. The translation results are reviewed and modified by native speakers (the researchers themselves).

3.4 Pilot test and Data collection

Even since scholars started to conduct cross-cultural studies, there has been a strong need for multi-language instruments. Sechrest & Fay (1972) pointed out that scale translation may have an impact on the effectiveness. Given that the original scales this study applies were in English and we translated them to Traditional Chinese and Vietnamese, we conducted a pilot test to verify the internal consistency.

A pilot test of the Vietnamese versions of the Simplicity and Certainty of Knowledge (SCK) and Source of Knowledge (SK) scales was conducted with 30 Vietnamese students. The results showed relatively low internal consistency, with Cronbach’s Alpha of .382 and .517 for SCK and SK, respectively. Several items exhibited low or even negative corrected item-total correlations (e.g., SCK5 and SK3). During the pilot test, some participants gave feedback about the difficulty of understanding the questions’ meaning, especially in SMEBS.

Based on these findings, the research team carefully revised and improved the Vietnamese translations of these scales to better align with the original meanings while ensuring clarity and cultural appropriateness for use in the main study. However, the construct Justification for Knowing (JK) demonstrated good reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha = .805) and therefore the Vietnamese translation was retained without modifications.

The pilot test results also showed that the Vietnamese translation of the NML scales exhibited good to excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s Alpha ranging from .842 to .920 across the four constructs: Critical Prosumption (α = .919), Functional Prosumption (α = .920), Critical Consumption (α = .900), and Functional Consumption (α = .842). These constructs can therefore be used directly in the main survey without further revision.

A separate pilot test was conducted with Taiwanese students to evaluate the internal consistency of the translated Traditional Chinese versions of the SMEBS (N = 15) and NMLS (N =12). For NMLS, results indicated that the Critical Consumption (α = .802), Functional Prosumption (α = .744), and Critical Prosumption (α = .818) scales demonstrated good to excellent reliability. However, the construct Functional Consumption showed relatively low internal consistency (α = .486)

However, same as the Vietnamese version, the SMEBS failed to meet the reliability requirements. The Simplicity & Certainty of Knowledge and Source of Knowledge construct exhibited lower reliability with (α =.527) and (α = .520), respectively. The Justification for Knowing scale showed marginally acceptable reliability (α = .645). These findings support the use of NMLS in the main study, while SMEBS requires further adaptation for cross-cultural validity.

Given that the purpose of this study is not on evaluating instruments or developing new ones, we still adopted SMEBS as our measurement to respect the original scales, while acknowledging this as the study’s limitation. We continued to collect the official data from two countries. An incentive (prize lottery) was given to promote the response rate. 53 responses from Vietnam and 48 responses from Taiwan were collected from May 17th to 30th, 2025.

4. Result

4.1 Reliability of data

Responses collected from Google form were compiled into readable files and imported into the SPSS tool for the analysis process. Though the pilot testing data did not yield acceptable reliability, we conducted the reliability testing with the official data again.

The main survey data collected from the SMEBS demonstrated improvement in internal consistency, compared to the pilot test. From Vietnam’s data,the SCK offered an acceptable level of reliability (α = .621), and the SK showed good improvement (α = .669), while JK remained good reliability (α = 761). As for Taiwan’s data, the Cronbach’s Alphas of all three constructs increased, while SK (α = .771) and JK (α =. 814) rose significantly and SCK (α = .583) slightly.

Despite the enhancement, certain items (e.g., SCK4, SCK5, SK3) may still warrant further review in future studies. These results might suggest that the enhanced translation process contributed to more coherent item responses, or the pilot test performance was due to low amounts of responses.

Regarding the NML measures, the main survey data show as good reliability as the pilot test. On Vietnam’s side, all four constructs showed good to excellent reliability: CP (α = .894), FP (α = .822), CC (α = .840), and FC (α = .745). Same on Taiwan’s side - CP (α = .818 ), FP (α = .818), CC (α = .870), and FC (α = .755).

4.2 RQ1: Examining the relationship between SMEB and NML

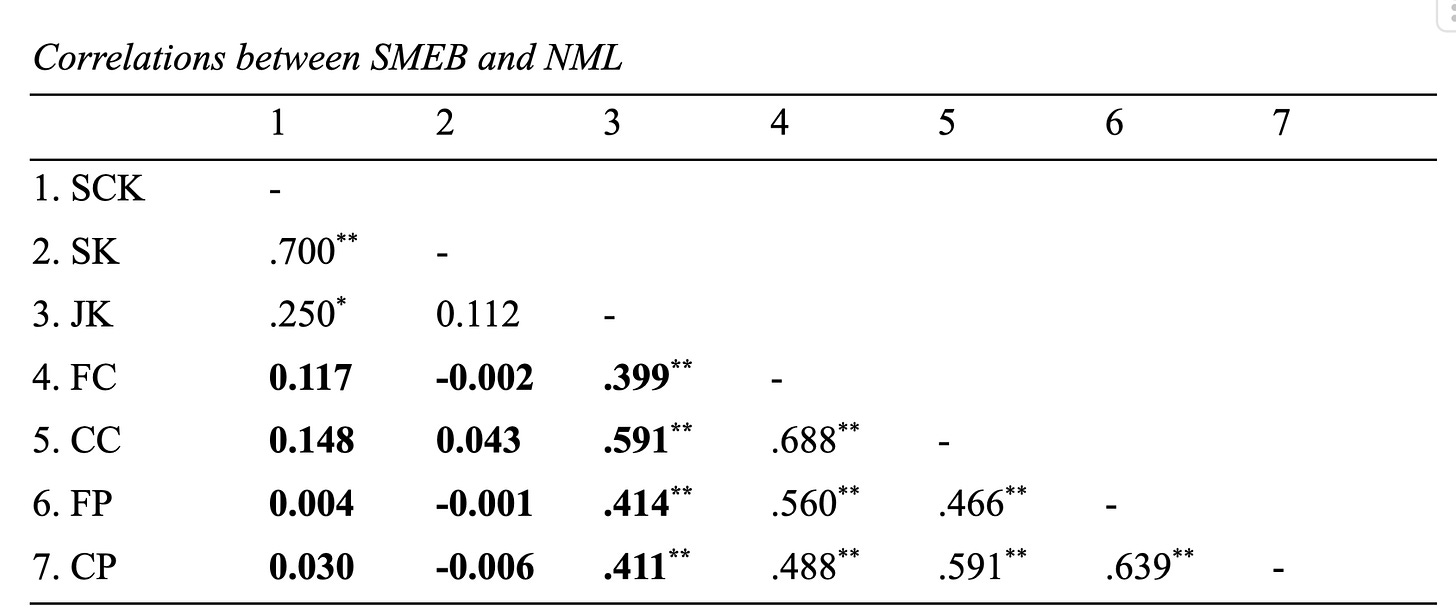

After running a Pearson correlation analysis, the result revealed that JK was significantly and positively correlated with all four dimensions of new media literacy, including FC (r = .389, p < .001), CC (r = .582, p < .001), FC (r = .419, p < .001), and CP (r = .380, p < .001). In contrast, SCK and SK showed no significant correlation with any literacy constructs.

Among the NMLS constructs, strong intercorrelations were found, notably between Functional and Critical Consumption (r = .693), and between Functional and Critical Prosumption (r = .667)

4.3 RQ2-1: Comparing Taiwan and Vietnam in SMEB.

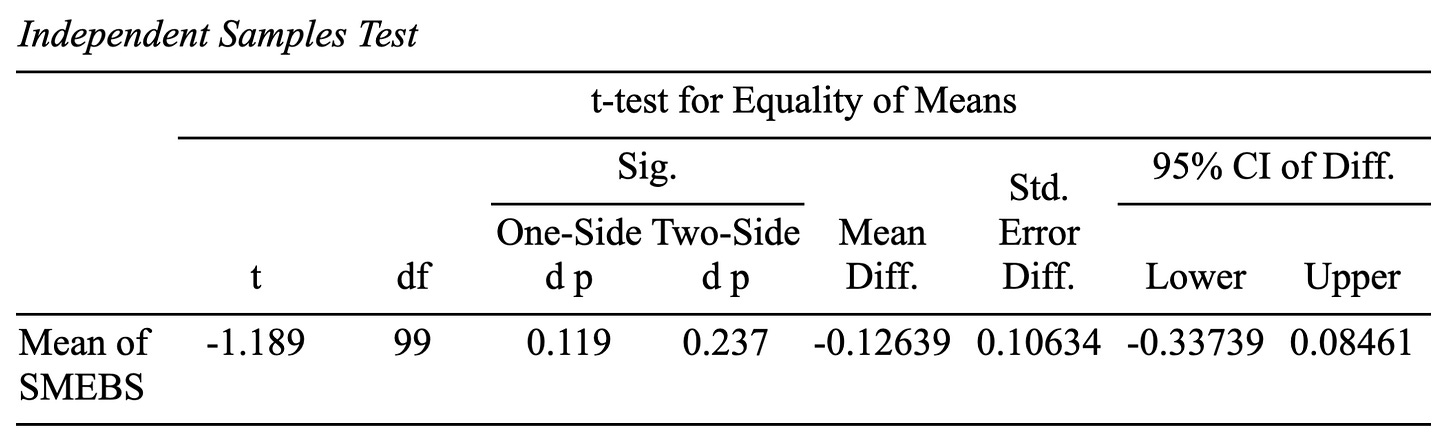

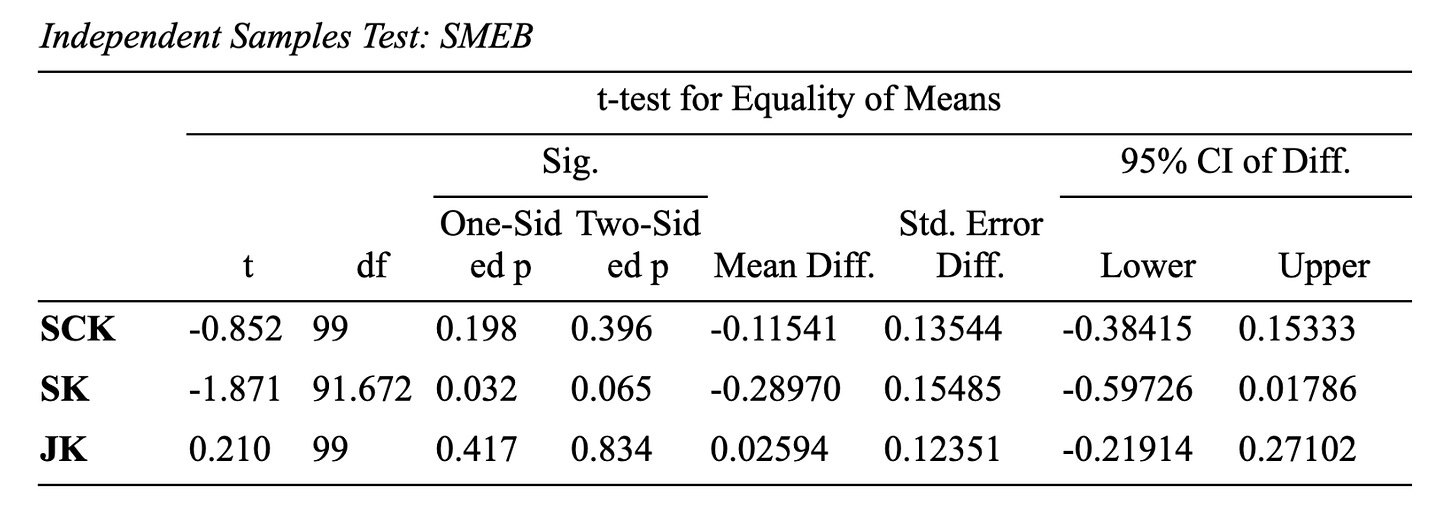

An independent sample t-test was conducted to compare the total mean of SMEBS between Vietnamese and Taiwanese students. The result p = .237 showed that there was no significant difference in SMEB between two countries.

When we break it down by the three aspects, there was no significant difference in all three constructs: Simplicity and Certainty of Knowledge, t(99) = -0.852, p = .396, Justification for Knowing, t(99) = 0.210, p = .834, and Source of Knowledge, t(91.67) = –1.871, p = .065.

4.4 RQ2-2: Comparing Taiwan and Vietnam in NML

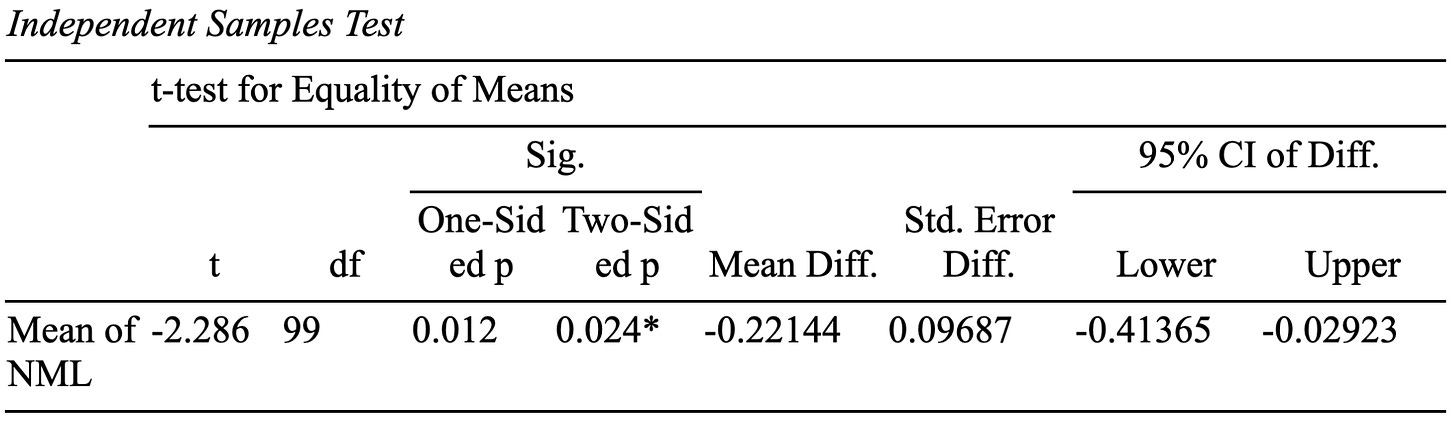

An independent sample t-test was conducted to compare NML between Vietnamese and Taiwanese students. The result p = .024 indicated that there was significant difference in NML between two countries. And Taiwan out-performed Vietnam in the overall NML.

If we break it down by the three aspects, results showed that Taiwanese students scored significantly higher than their Vietnamese counterparts in Functional Prosumption (t(99) = –3.039, p = .003) and Critical Prosumption (t(99) = –2.317, p = .023). No significant difference was found in Critical Consumption (p = .532), while Functional Consumption showed a near-significant trend (p = .052). These findings suggest that Taiwanese students may be more engaged and critically aware in content production on social media.

5. Conclusion

Out of the three constructs in social media-epistemology belief, we found that Justification of Knowing (JK) matters the most, while the other two factors are relatively unrelated to the literacy outcomes.

While there are significant differences between countries in terms of media literacy performance, the main difference comes from the prosumption aspects. On the other hand, epistemic beliefs in the social media context appear to be culturally neutral, suggesting similar beliefs about social media knowledge across the two selected countries, Taiwan and Vietnam.

6. Discussion & Limitation

As the study motivation presumes, Taiwan and Vietnam present different performance in most media literacy skills. This may reflect that the education initiatives made by the government were successful. On the other hand, Vietnam’s relatively tight media landscape and political environment can potentially explain the lower prosumption skills.

The state’s regulation over online content, restrictions on public expression could discourage critical participation, especially in politically sensitive domains. This sociopolitical context may shape not only behavioral norms but also epistemic stances toward information sharing online.

In terms of practical implication, the current study informs the importance of teaching justification strategies while JK was highlighted in the result. Examples include knowledge source comparison, logic checks, etc. It also suggests that only empowering students with tools or mindsets can be insufficient.

It also aligns with the AIR Framework, which indicates that reliable epistemic processes, such as source evaluation, critical reasoning, and information synthesis, are activated and shaped by an individual’s epistemic aims and ideals.

In this case, the strong relationship between Justification for Knowing and media literacy suggests that students who value justification are more likely to engage in sophisticated media-literacy behaviors, especially under epistemically complex conditions like social media environments.

The researchers would also like to acknowledge a few limitations in this study. First of all, as the pilot test results suggest, the reliability of the translated SMEB scale did not meet the requirements. Even though the official survey showed better internal consistency, there is still improvement to be made.

During the pilot test process, a few participants gave feedback that the questions in the SMEBS were difficult to understand. Some were due to the phrases used in the questions and some were because of the reverse question design (the original scale contains 7 reverse items out of 15 total items).

We believe that distinct online media environments can cause very different understanding toward the descriptions of such questions. Therefore, even though the size of collected data was modest, there is a need of re-evaluating the SMEBS under different cultural and language contexts. Future researchers can explore the possibility of constructing new scales to measure individuals’ social media-specific epistemology belief.

References

Bartsch, A., Neuberger, C., Stark, B., Karnowski, V., Maurer, M., Pentzold, C., ... & Schemer, C. (2025). Epistemic authority in the digital public sphere. An integrative conceptual framework and research agenda. Communication Theory, 35(1), 37-50.

Barzilai, S., & Chinn, C. A. (2024). The AIR and Apt-AIR frameworks of epistemic performance and growth: Reflections on educational theory development. Educational Psychology Review, 36(3), 91.

Bromme, R., Kienhues, D., & Porsch, T. (2010). Who knows what and who can we believe? Epistemological beliefs are beliefs about knowledge (mostly) to be attained from others. Personal epistemology in the classroom: Theory, research, and implications for practice, 163-193.

Celik, I., Muukkonen, H., & Dogan, S. (2021). A model for understanding new media literacy: Epistemological beliefs and social media use. Library & Information Science Research, 43(4), 101125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2021.101125

Celik, Ismail. (2019). Social Media-Specific Epistemological Beliefs: A Scale Development Study. Journal of Educational Computing Research. 58. 073563311985070. 10.1177/0735633119850708.

Chen, D. T., Wu, J., & Wang, Y. M. (2011). Unpacking new media literacy. Journal of Systemics Cybernetics and Informatics.

Guarascio, F., & Nguyen, P. (2024). Telegram ‘surprised’ as Vietnam orders messaging app to be blocked. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/society-equity/vietnam-acts-block-messaging-app-telegram-government-document-seen-by-reuters-2025-05-23/

Hofer, B. K. (2008). Personal epistemology and culture. In Knowing, knowledge and beliefs: Epistemological studies across diverse cultures (pp. 3-22). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

King, P. M., & Kitchener, K. S. (2012). The reflective judgment model: Twenty years of research on epistemic cognition. Personal epistemology, 37-61.

Koc, M., & Barut, E. (2016). Development and validation of New Media Literacy Scale (NMLS) for university students. Computers in human behavior, 63, 834-843.

Le, V. T., & Hutchinson, J. (2022). Regulating social media and influencers within Vietnam. Policy & Internet, 14(3), 558-573.

Lin, T. B., Li, J. Y., Deng, F., & Lee, L. (2013). Understanding new media literacy: An explorative theoretical framework. Journal of educational technology & society, 16(4), 160-170.

Mercy Corps. (2019, 12 11). The Weaponization of Social Media. https://www.mercycorps.org/research-resources/weaponization-social-media

National Security Bureau, R.O.C.. (2025, January 5). Analysis on China’s Cyberattack Techniques in 2024. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://www.nsb.gov.tw/en/#/%E5%85%AC%E5%91%8A%E8%B3%87%E8%A8%8A/%E6%96%B0%E8%81%9E%E7%A8%BF%E6%9A%A8%E6%96%B0%E8%81%9E%E5%8F%83%E8%80%83%E8%B3%87%E6%96%99/2025-01-05/Analysis%20on%20China’s%20Cyberattack%20Techniques%20in%202024

Pillow B. H. (1999). Epistemological development in adolescence and adulthood: a multidimensional framework. Genetic, social, and general psychology monographs, 125(4), 413–432.

Po-Chin Huang (2020). The Influence, Employment and Establishment of Capacity of Weaponized Social Media. National Defense Journal, 35(3), 1-30. https://doi.org/10.6326/NDJ.202009_35(3).0001

Sharon, T., & Encarnación, M. (2024). Social Media & Declining Trust: An Epistemic Challenge for Emerging Adults? Emerging Adulthood, 12(3), 358-371. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968241234091 (Original work published 2024)

Taiwan Ministry of Education. (2023, 3). Whitepaper of media literacy education in the digital age. Retrieved 1 11, 2024, from https://ws.moe.edu.tw/001/Upload/3/relfile/6315/88728/acae722a-d0d8-4a48-b86f-a7962c905c77.pdf

Taiwan Network Information Center. (2024, 10). 2024 Taiwan Internet Report. Retrieved 12 10, 2024, from https://report.twnic.tw/2024/en/TrendAnalysis_issueInsight.html

U.S. DEPARTMENT of STATES. (2023, September 28). How the People’s Republic of China Seeks to Reshape the Global Information Environment - United States Department of State. State Department. Retrieved January 11, 2025, from https://www.state.gov/gec-special-report-how-the-peoples-republic-of-china-seeks-to-reshape-the-global-information-environment/

Uslu, N. A., & Durak, H. Y. (2022). The relationships between university students’ information-seeking strategies, social-media specific epistemological beliefs, information literacy, and personality traits. Library & Information Science Research, 44(2), 101155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2022.101155

Vu, V. T. (2024). Media literacy, trust in government and vaccine readiness: A study among Vietnam’s youngsters. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 16(3), 120-132. https://doi.org/10.23860/JMLE-2024-16-3-9