Case share: Tackling misinformation via a gamified approach

A study developed a game asking users to “produce” fake news, and it actually empower them with the resistance against fake news.

Under the digital era, manipulated information has been a huge trouble to the civic society. People got influenced by so called misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation made it very difficult to reach a consensus on public topics. Polarization and

Various approaches have been implemented and tested to tackle this challenge. While we started to realize that we can never catch the speed of producing fake news, researchers turned their approach to empowering the media audience or social media users with better competence of recognizing these messages.

Following this approach, a group of scholars from University of Cambridge designed an online game that applies the psychological inoculation theory. They wanted to know if such a gamification approach has educational effect on people’s information resilience.

But first, what is the concept of psychological inoculation?

The inoculation theory is proposed by William J. McGuire (1961). It applied the concept of “vaccine” in the public health area, which helps people become immune to certain virus by providing a tiny amount of it.

When it’s applied to the psychology field, it means we expose individuals to a weakened version of statement that is against their knowledge beliefs. The process is called “prebunking”. By doing so, the individual’s brain kind of get alerted to these types of information, and become more resistant against further manipulated ones.

How is the game “Bad News” designed?

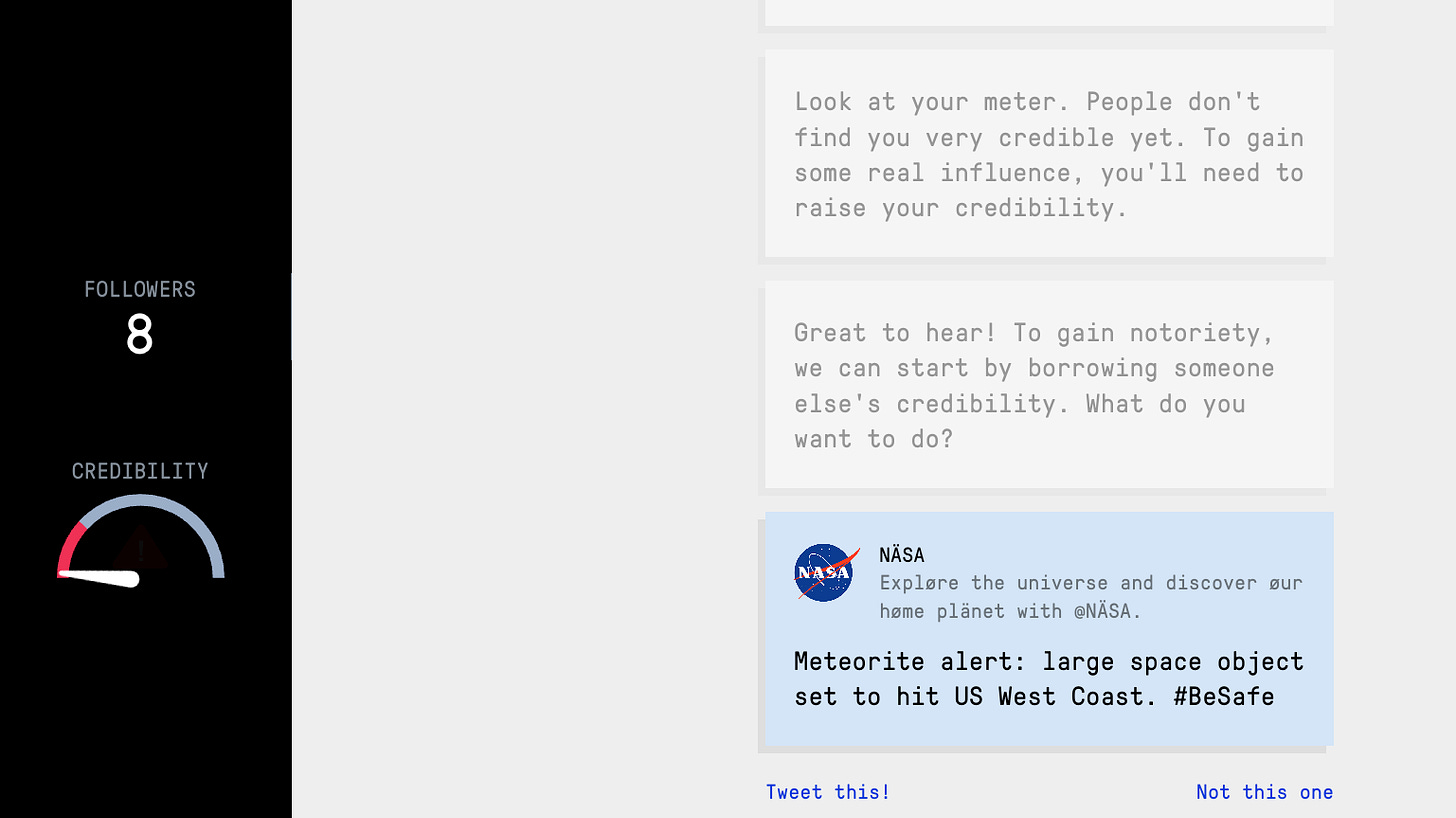

So how does the game work? The players are given an ultimate objective where they have to build an online media that spread fake news. The goal is to gain the audience trusts. Through the game experience, the system will provide the users series of options of actions they can take. For example, the news headlines that players want to use or the tweet content they want to post.

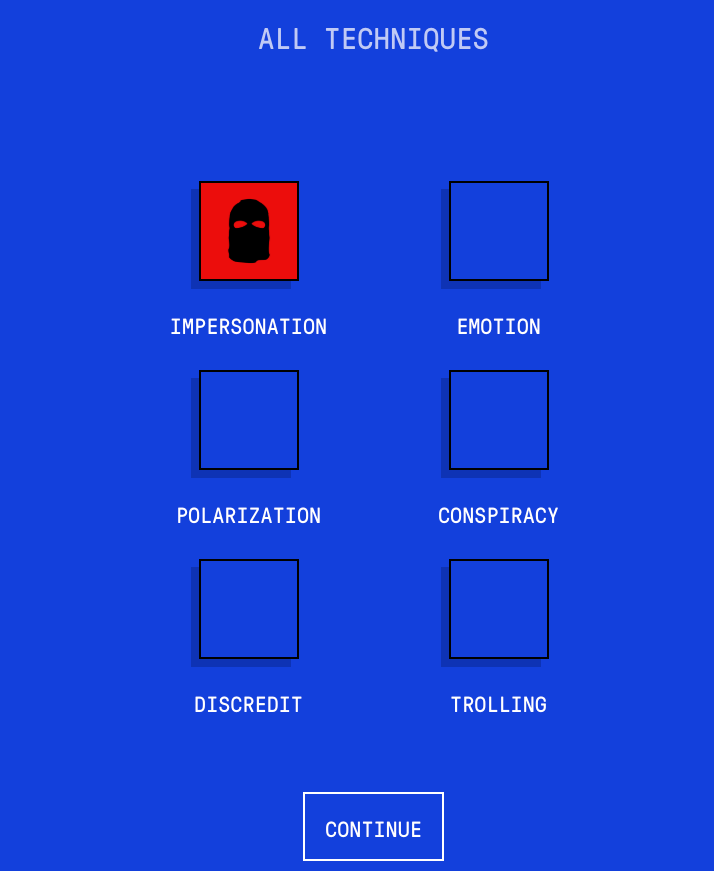

On the other hand, based on the theories, they integrate six different approaches that guide the players to reach their goals. These are the most common strategies identified that problematic media would use. They are:

Impersonating people online.

Using emotional language.

Group polarization.

Floating conspiracy theories and building echo chambers.

Discrediting opponents.

Trolling people online and false amplification.

You can play this game at https://www.getbadnews.com/en

The experiments and findings

To test if the game actually works, they conducted three different experiments.

Study 1 (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2019)

First, they compare the abilities of a same group of users before and after playing the games. Players are prompted to rate the reliability of a series of fake news before they play game. Afterward, they need to rate them again.

Result found that the reliability scores were significantly lowered after the game, which means that the players are more abled to recognize the problematic information. More importantly, this effect applies to all demographic groups (gender, political tendency, ideology, etc.)

Study 2 (Basol et al., 2020)

Second, they compare two groups of people. One group would plays the game “Bad news”. The other group would just play an irrelevant game “Tetris”.

Similarly, all individuals are prompted to rate reliability before and after the games. But this time, they also need to rate “how confident they are with the score they give to each news”.

They compare the pre and post scores again. The result shows that not only are the reliability scores from the groups who played “Bad News” lowered significantly more than the other group. But, their confidence rose as well! Especially on those news they “correct” their opinions.

Study 3 (Maertens et al., 2021)

Lastly, you might wonder how long can these effected last? After all, the previous experiments were done in a very short period of time (the game takes approximately 15 minutes). So the scholars conducted longitude studies.

To test this, they extend the experiments to up to 3 months. In one of them, participants were provided a post-test right after the game and another one 9 weeks after that. In another experiment, they provided a series of post-tests at multiple time points: 1 week, 5 weeks, and 13 weeks after the game.

Interestingly, the inoculation effect decayed in the first experiment. However, the decay in the second one wasn’t significant. This shown that the effect can last even months after the game, but only if the individuals are exposed to environments every once a while.

What does this inform us?

As an educator, I have talked to many teachers who care about this topic. One of the biggest struggles is how to effectively provide instructions in classes.

I once worked with a group of pre-service teachers and they were testing out a curriculum where they wanted to guide the students on how to spot problematic information in news. They designed a series of written news and invited the students to circle the sentences that could be incorrect (these are not actual news identified online, but materials made for lesson use).

The materials were written in en exaggerated way because they wanted to make it possible for the students. However, we quickly found out that lacking of the real experiences of “fake news”, the students have nowhere to begin with.

The case of this gamified approach have us rethink an innovative way to facilitate such curriculum. By creating a virtual but real experience for the learners, it serves as a starting point for teachers to bring out this important topic.

References

Basol, M., Roozenbeek, J., & Linden, S. van der. (2020). Good News about Bad News: Gamified Inoculation Boosts Confidence and Cognitive Immunity Against Fake News | Journal of Cognition. https://doi.org/10.5334/joc.91

Maertens, R., Roozenbeek, J., Basol, M., & van der Linden, S. (2021). Long-term effectiveness of inoculation against misinformation: Three longitudinal experiments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 27(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000315

McGuire, W. J. (1961). Resistance to persuasion conferred by active and passive prior refutation of the same and alternative counterarguments. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63(2), 326–332. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0048344

Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2019). Fake news game confers psychological resistance against online misinformation. Palgrave Communications, 5(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0279-9